Types of exercise

Recovery

Fitness myths

Evlo Programs

BODY COMPOSITION

All

Browse by category

Browse by category

Ab exercises: What can stay and what should go?

Exercise selection can get really confusing, especially when it comes to targeting the abdominals! And there are a lot of myths when it comes to ab work. Check out Dr. Shannon’s Fit Body, Happy Joints episode all about those myths here.

The intention of this post is to present abdominal exercises in a non-biased, free-of-fitness-culture-myths way. Here at Evlo, we look at exercises through a biomechanical lens. Meaning, we look at the various levers of the body at play, the direction of the force, and errant forces to the surrounding joints.

Anatomy

To give context to the discussion and exercises presented, let’s first dive into the anatomy of the two different abdominal muscles that we will focus on:

- Transversus Abdominis

- Rectus Abdominis

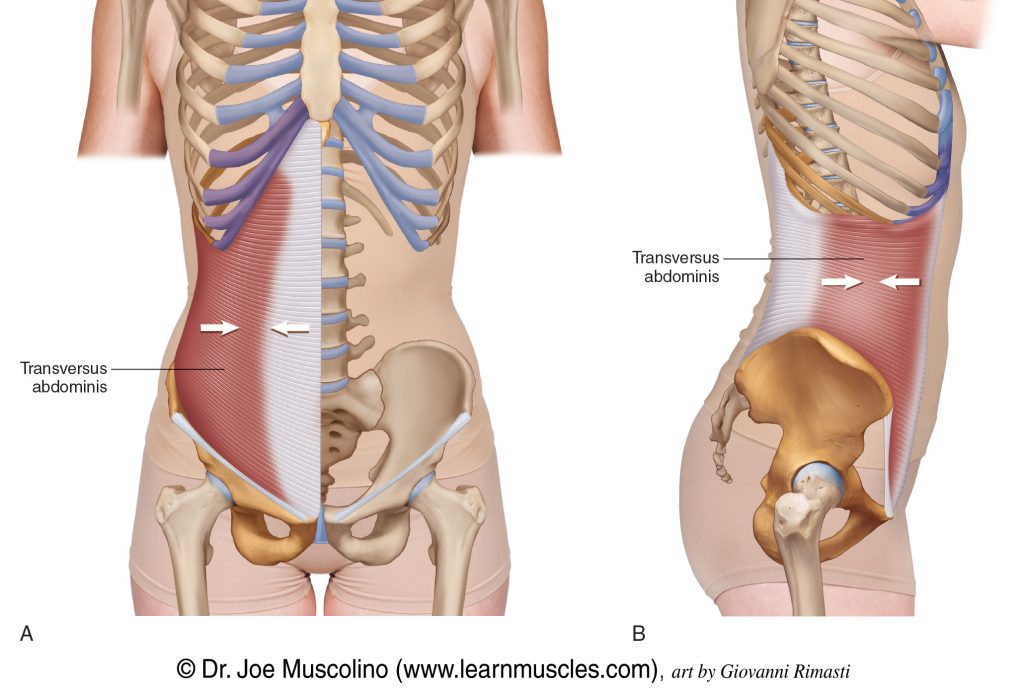

Transversus Abdominis (TrA)

The transversus abdominis is the deepest layer of abdominal musculature and important for lumbar stabilization. This muscle originates on both the anterior and posterior aspect of the trunk including the (1) anterior two thirds of iliac crest, (2) lateral third of inguinal ligament, (3) thoracolumbar fascia, and (4) costal cartilages of the lower six ribs. This muscle inserts in the anterior portion of the trunk at the linea alba (the cartilaginous line along the center of your abdominals), pubic crest, and pectineal line. One of the main functions of the muscle is to exert pressure within your abdominal cavity to oppose pressure applied by gravity to your visceral organs!

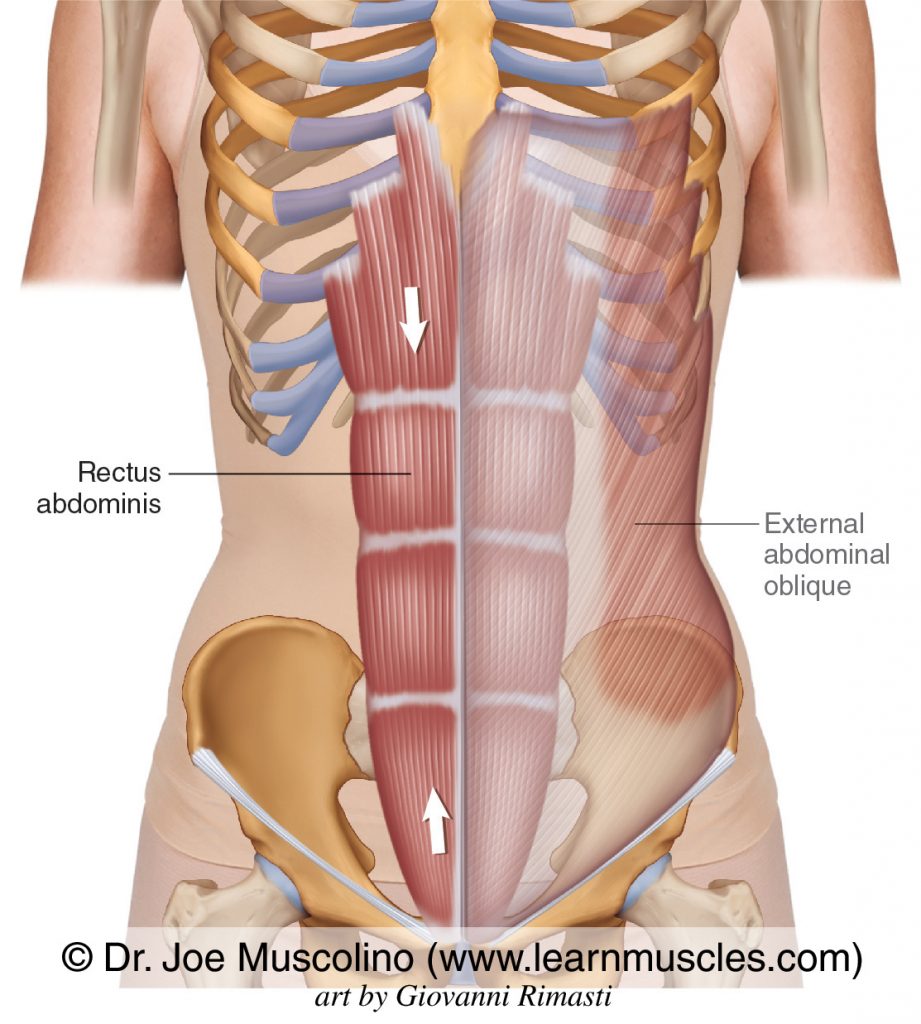

Rectus Abdominis (RA)

The rectus abdominis originates on the pubic crest, pubic tubercle, and symphysis. One can palpate the pubic tubercle by placing finger tips below the belly button and applying a downward pressure until reaching this bony prominence. We believe that knowledge of these origin/insertion points aids with improved muscle activation through palpation and imagery! The rectus abdominis inserts on the anterior surface of the xiphoid process (bottom of the sternum!!) as well as the fifth, sixth, and seventh costal cartilages. The primary function of this muscle is lumbar flexion.

Opposite Position Loading

It is also important to understand the concept of opposite position loading. You most accurately load/target a muscle when the force from external resistance directly opposes the line of pull of the muscle. The line of pull can be from insertion to origin of the muscle or vice versa. External resistance for abdominal exercises typically comes from the downward force of gravity. This is one of the main factors that we use to determine effectiveness of the exercises we will sort through below.

Muscle Contractions

Types of muscle contractions also play a role in effectiveness of the exercise for the purpose of muscle hypertrophy (muscle growth). Isometric contractions occur when a muscle statically contracts to maintain a stable position (think holding midway up with a biceps curl). Concentric contractions occur dynamically as the muscle shortens (origin and insertion get closer together) while loaded. Eccentric contractions also happen dynamically as the muscle lengthens (origin and insertion get further apart) while loaded. We get the most motor unit recruitment and load to the muscle from an eccentric contraction and the least from an isometric contraction.

When breaking down exercises, I categorized some of the most common “core” exercises into 3 different sections

- Stabilization exercises (mainly targeting TrA)

- Exercises for effective RA hypertrophy

- Exercises that are purported as abdominal exercises, but primarily target a different muscle group

Stabilization

Stabilization exercises are important for laying a strong core foundation. I will break down how these exercises work, the benefits of performing these exercises, the frequency at which these exercises can be performed, and review the exercises themselves.

How the exercises work

Abdominal stabilization exercises typically work through a process called neuromuscular re-education. Because of the rigid positions we find ourselves in and the activities we do, we often become quite disconnected from our abdominal muscles, especially our TrAs.

Our nervous system completely controls our muscles’ ability to contract and to relax. When the brain-body connection dampens, this ability decreases. Neuromuscular re-education involves re-establishing this brain-to-muscle connection.

Benefits

Re-establishing this connection with our abdominals is advantageous for many reasons. Based on the TrA positioning between the ribcage and pelvis, our control of this muscle can significantly affect our posture. With improved control of this muscle (along with the internal obliques), we are better able to stack the rib cage over the pelvis. In general, this helps to take us out of an overly lordotic position in the lumbar spine.

Having the ability to stack the rib cage over the spine allows us to improve our breathing as well as our pelvic floor function. In this position, the diaphragm and pelvic floor are better able to descend and ascend appropriately.

This position also allows us to better tap into our parasympathetic (rest, digest, recover) nervous system. A rigid, overly extended posture upregulates the sympathetic (fight-or-flight) nervous system because of its effect on the vagus nerve! Being in a constant state of fight-or-flight dampens our ability to recover from external stressors in our life, including our workouts!

Improved connection with our deeper abdominal muscles also allows for improved trunk control and pelvis stability. And often with improved stability comes improved mobility!! This is because our nervous system senses less of a threat and allows for greater ranges of motion.

This connection can sometimes decrease the appearance of a bulge of the lower portion of your abdomen. But only the portion that is exacerbated by being overly lordotic. Remember that we cannot spot treat fat and these exercises should not be used in hopes of “dissolving your mom pooch”. Also, can we all agree to stop using the phrase mom pooch?!? (Looking at you, Tiktok!)

Frequency

Many stabilization exercises can be done daily. This is because the implication to the muscle tissue differs as compared to hypertrophic exercises.

Typically, there is less breakdown of muscle tissue with stability exercises as you are not tapping into the larger type II muscle fibers. Exercises that function through neuromuscular re-education (like many exercises you may receive in physical therapy) are meant to be performed daily in order to strengthen that brain-to-muscle connection.

Stabilization Exercises

Examples of stabilization exercises to incorporate into your regular routine:

- Breathwork in many positions:

- Inhale through the nose

- Exhale through the mouth

- Imagine drawing the pelvic floor up and in as your slowly exhale

- Foundational core and progressive leg variations

- Dead bug

- Bird dog

- Modified planks with focus on breathwork explained above

- Pallof press

The following are exercises that do help with stabilization, but might not be worth the risk:

- Leg lowers: This exercise primarily loads the hip flexors while placing a significant strain on the lumbar spine. The psoas muscle, one of your hip flexors, attaches to the anterior portion of the lumbar spine and pulls the spine further into lordosis as the legs lower. The abdominals activate isometrically in order to counter this significant force. Listen to Dr. Shannon’s FBHJ episode with Doug Brignole for further breakdown here.

- Regular planks: Many muscle groups are having to stabilize at once in a full plank. While this is not necessarily a bad thing, it can distract from the task at hand. The significant downward force from gravity to the lumbar spine may also not be worth the risk as the legs are extended. Form is very important when it comes to the full expression of a plank.

Rectus abdominis muscle hypertrophy

As described under “opposite position loading”, you must place the force or load directly opposite to a muscle to most effectively load it. When we effectively opposite position load the abdominals + allow them to contract both concentrically and eccentrically, we are able to tap into the type II muscle fibers. When paired with appropriate recovery time, these are the types of exercises that make the biggest difference when it comes to actual muscle growth of the RA.

Frequency

As with any muscle group, the abdominals should not be worked with the intention of muscle hypertrophy more than 2 (max of 3) times per week. It is a common misconception that you should work a muscle more frequently in order to gain faster results. However, when a muscle group is effectively targeted in the way described above, adequate time is needed for the muscle to rebuild through the anabolic processes before it is targeted again. Overuse of the abdominals is all too common in the fitness industry!

Ball crunches

With ball crunches, we are able to use gravity as our external load to directly oppose the abdominal muscles as we crunch up. A small pilates ball is placed behind the low back. On an inhale, we lower the trunk over the ball. With an audible exhale, the trunk curls up in a controlled fashion.

Hand position plays a significant role in how much we are loading the abdominals.

Here are the positions from least to most load to the abdominals:

- Elbows fixed by your side; isometric contraction of the abdominals

- Hands behind your knees or grabbing the sides of your mat

- Hands moving beside your legs

- Hands across your chest

- Hands behind your head

As these hand positions are progressed, more of your body mass is required to lift against gravity, therefore increasing the load to your muscles! Use the hand positions that feel most challenging to you on any given day while still maintaining control of the motion. You can utilize these modifications to eliminate neck discomfort during the exercise. Steps (1) and (2) are great places to start!

Considerations

One thing to look for as you perform a ball crunch is “doming” or “coning” down your midline. This typically signifies a lack of deeper abdominal activation during the motion. If you notice this doming even with your elbows fixed by your side, I would recommend beginning with stabilization exercises and/or working one-on-one with a physical therapist!

We use the cues “knit rib cage towards your belly button” and “zip pubic bone up towards your belly button” to approximate abdominal muscle origins and insertions. In order to ensure involvement of the deeper abdominal muscles (TrAs and internal obliques) during this exercise, we bring specific attention to your breath. We know the “angry librarian” or “shhh” breath can seem silly, but it’s through this breath that we can increase intra-abdominal pressure to target our deeper abdominal muscles. As a bonus, this allows for decreased activation of the accessory breathing muscles of the neck and more focused activation of the abdominals

Compared to regular crunches on the ground, ball crunches allow us to go through a fuller range of motion. When we extend over the ball, we are able to achieve that eccentric contraction of the RA. Talk about bang for your buck!

Ball crunches also allow us to better avoid over activation of the hip flexors. In fact, you should experience little to no change in hip flexion in a standard ball crunch.

Prone and Quadruped Swiss Ball Exercises

A 2010 study analyzed various swiss ball exercises as compared to traditional crunches using Electromyographic (EMG) data. A roll-out, performed with knees on the ground and elbows to the ball, as well as a pike, performed with hands on the ground and feet on the ball, were found to activate the RA the most.

For the roll-out, a significant eccentric force is placed through the RA as the ball is rolled away from the knees. This could be a great exercise to incorporate while pregnant, but special attention should be paid to avoid excessive lumbar lordosis as you roll the ball away from your knees.

For the pike, a significant concentric force is placed through the RA as the hips come up towards the sky, pushing against the downward force of gravity, and approximating the origin and insertion of the RA.

However, the pike does not come without its own set of risks. The pike requires significant pressure through dorsiflexed wrists as well as balance to maintain the position on the ball. The lumbar spine can also potentially be at risk in the starting position, as described with the regular plank above. It may not be worth the risk when ball crunches are an available option!

Exercises that induce little to no additional abdominal activation

I’ve included the following exercises under this category due to the lack of opposite position loading or stability required of the abdominals.

- Knee ups while in a static hang (mainly targets the hip flexors)

- Standing or seated ab work like marching (mainly targets the hip flexors)

- Russian twists/bicycles (meant to target the obliques)

- Instead try:

Evlo Burn Classes

Our Burn classes (and classes that include Burn in the title) are a great way to achieve both stability and muscle hypertrophy of the abdominals. We include the most effective and safe abdominal exercises while leaving out the “fluff”. Try a free Burn class here!

References

How to train your abs/core & 10 core myths: https://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2010.3073

Swiss ball exercises: prone a good or better than traditional crunch: https://www.jospt.org/doi/pdf/10.2519/jospt.2010.3073

Can you train your lower abs?: https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/69-can-you-train-your-lower-abs-with-doug-brignole/id1561242280?i=1000569098454

Join our community where you no longer need to deplete yourself to see fitness results.